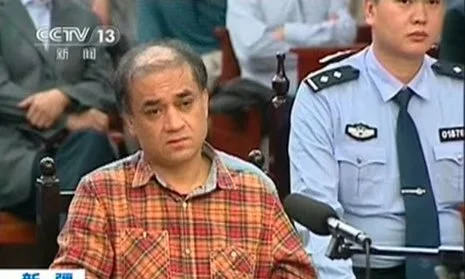

Prominent Uyghur academic Ilham Tohti jailed for life

With its shocking outcome, this trial might result in an increase in violence in the Xinjiang region, where protests for the mistreatment of a moderate voice could motivate the more radical factions.

When poet Abduxaliq Uyghur penned the verses of “Oyghan” in 1921, the times were dire for the Uyghur minority in Western China. The chaotic political vacuum in which the Xinjiang region found itself at the end of the Qing dynasty and during the first years of the Republican era, provided the ideal hotbed for the ever-latent Pan-Turkic idea.

Hey, poor Uyghur, wake up, you have slept long enough, You have nothing, what is now at stake is your very life. If you don’t rescue yourself from this death, Ah, your end will be looming, your end will be looming […]

Abduxaliq Uyghur, Oyghan (Wake Up!), 1921

Not much has changed with the demise of the Kuomintang and the rise of the Democratic Republic of China, and Uyghur identity has remained fragmented, split between Pan-Turkism and Pan-Islamism, with a lack of a credible and unifying leadership that could sit at the negotiating table with its powerful Chinese counterpart. Economist Ilham Tohti, an academic who has always championed a moderate view, is undoubtedly one of the most authoritative voices of its people having taught at Minzu University of China in Beijing (formerly Central Nationalities University) and having co-founded Uyghur Online, one of the few platforms promoting a mutual exchange of opinions and information between Han Chinese and Uyghurs.

Tohti, 44, was the recipient of the 2014 PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award, but he was never able to accept his prize, having been imprisoned in January following a string of harassment incidents and intimidations which concluded with him not being able to see his lawyer for many months. On September 17, a trial began in which a guilty verdict appeared inevitable, but almost nobody took into consideration the possibility that Ilham Tohti could indeed spend the rest of his life behind bars.

US Secretary of State John Kerry’s reaction to the life sentence was one of surprise and disdain, but what worries observers and human rights associations right now is the fear that this sentence could mark the beginning of a new stage of repression, not only in Xinjiang, but also in other areas of the Middle Kingdom. Although Tohti has denied the charges, he was accused of being the political arm of a not better-identified jihad conspiring against the unity of the Chinese state by posing as the ideologist of an armed separatist faction. The links between Ilham Tohti, his students (some of them imprisoned as well) and the violent fringes of Xinjiang’s Uyghur ethnic group are yet to be proven.

What seems to worry the authorities is the escalating ethnic tension between the two main groups (the Uyghurs and the Han Chinese) which culminated in 2009 in a series of riots in the capital city of Ürümqi, where almost 200 people were killed, and more than 800 were injured. Human rights organisations, such as the Uyghurs Human Right Project or The International Uyghur Human Rights and Democracy Foundation maintain that the vast majority of the Uyghurs do not advocate the separation of their region from the rest of China, but rather, demand fair treatment for their ethnic group. Predominantly Muslim, the Uyghurs appeal for freedom of faith and expression in an area where women are prevented from wearing headscarves and only state-approved editions of the Quran can be read.

Chinese authorities, on the other hand, have accused the Uyghur minority of plotting to erode Chinese control in the region through a series of attacks. They blame them for the recent mass stabbing at Kunming railway station and 2013’s suicide attack in Tiananmen Square. However, as is always the case in China, investigations following the attacks have remained secret and reporting on the findings has been strictly controlled by the Government.

According to Katy Glenn Bass, deputy director of the PEN American Centre, “[…] one of the tragedies of this whole situation is that if the Chinese government was more reasonable, Ilham Tohti could be one of their greatest allies — this is a peaceful, moderate, thoughtful scholar who has spent his whole life trying to find solutions to China’s ethnic tensions”.

Li Fangping, one of Mr Tohti’s lawyers, recently revealed to the New York Times that “Mr. Tohti is an advocate for Uighur rights and religious freedom for the Uighur people, but he was never an advocate for Xinjiang independence or any kind of separatism”. So, could a call for equality and a persistent demand for justice pose a threat to the stability of the Chinese state? According to the reaction of the Chinese Government, it can.

“I have relentlessly appealed for equality for Uyghurs in regards to their individuality, religion, and culture”, Mr Tohti stated in January. “I have persistently demanded justice from the Chinese government. However, I have never pursued a violent route and I have never joined a group that utilized violence”.

According to Maya Wang, of Human Right Watch, speaking to The Telegraph, it would be "hard to stick a charge like terrorism on him. Even calling him a separatist is a problem. He is known for his very measured, moderate criticism of government policy in Xinjiang, pointing out, for example, that the policy of Han Chinese migration needs to be re-evaluated in light of the unemployment in Xinjiang," she added.

With its shocking outcome, this trial might result in an increase in violence in the Xinjiang region, where protests for the mistreatment of a moderate voice could motivate the more radical factions which, in turn, would feel legitimated in resorting to disorders to try and overturn a regime which does not intend to loosen the yokes of freedom of expression and social equality. In Xinjiang as well as in other areas of the troubled outskirts of the empire.